ACTIONS / POSTURE / GESTURE

Sweeping wrists, crouched legs and bent spines. Bangles clinking, fingers dusted with powdered rice.

In these subtleties lies a daily ritual, a way of life for many Indian women. The creation of a kolam.

In every gesture, a story unfolds. Actions become poetry when intention and motion intertwine.

This could be the slow, sacred art of being alive.

Filter through the videos to look into the various nuances of gestures, materials and ways in which rangolis can be drawn.

From Analog to Digital

In my own attempts to draw kolams physically, stooping over a tile floor with rice flour pinched between thumb and forefinger, I was quickly confronted with the gap between conceptual understanding and embodied knowledge. My hands struggled. The lines wavered, symmetry slipped, and the wet flour lay in uneven clumps. What felt like a simple gesture when watching others perform it- a graceful sweep of the hand, a confident curve- turned into a halting, awkward sequence when I tried to replicate it. Without years of practice and a lack of intuition, my fingers lacked finesse, and my body, untrained in the rhythms of kolam-making, resisted the flow.

This difficulty reminded me that gesture in kolam is not merely a motor skill; it is memory, ritual, and spatial orientation, all carried in the body. Drawing a kolam well is less a matter of seeing and more a matter of moving. It’s a form of knowledge embedded in the shoulders, the spine, and the fingertip.

↓ In the interactive sketch below, the act of drawing a kolam is mediated through a camera and a machine learning model that tracks hand gestures.

The result is not a perfect replication of human motion but a distorted echo of it. The misalignment between where your hand moves and where the kolam appears reflects the difficulty of translating embodied, tacit gestures into computational logic. Something always shifts. The delay, the drift, the spatial mismatch all echo the broader challenge of encoding a living, sensory practice into the structured demands of code. Rather than correct this, I let the distortion remain visible, a trace of translation.

From Hand to Machine

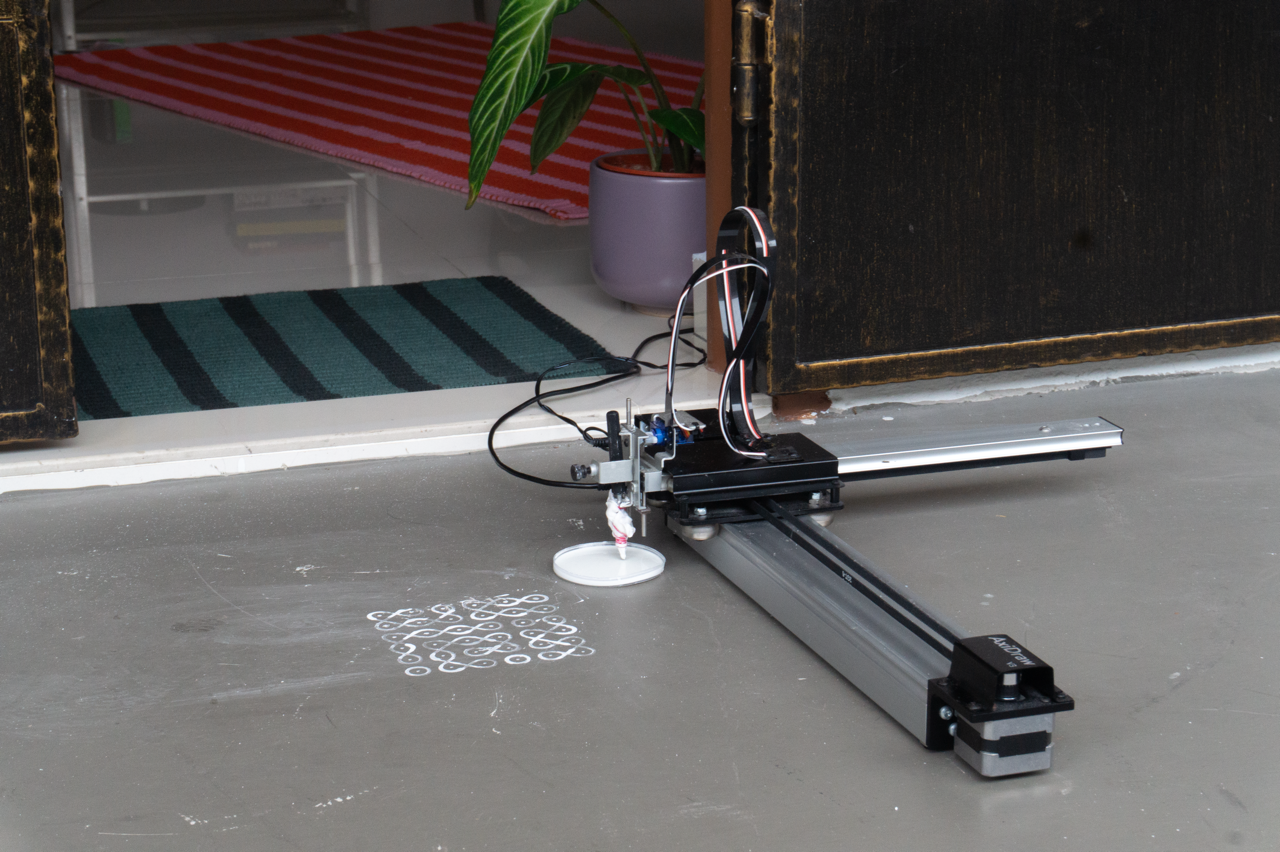

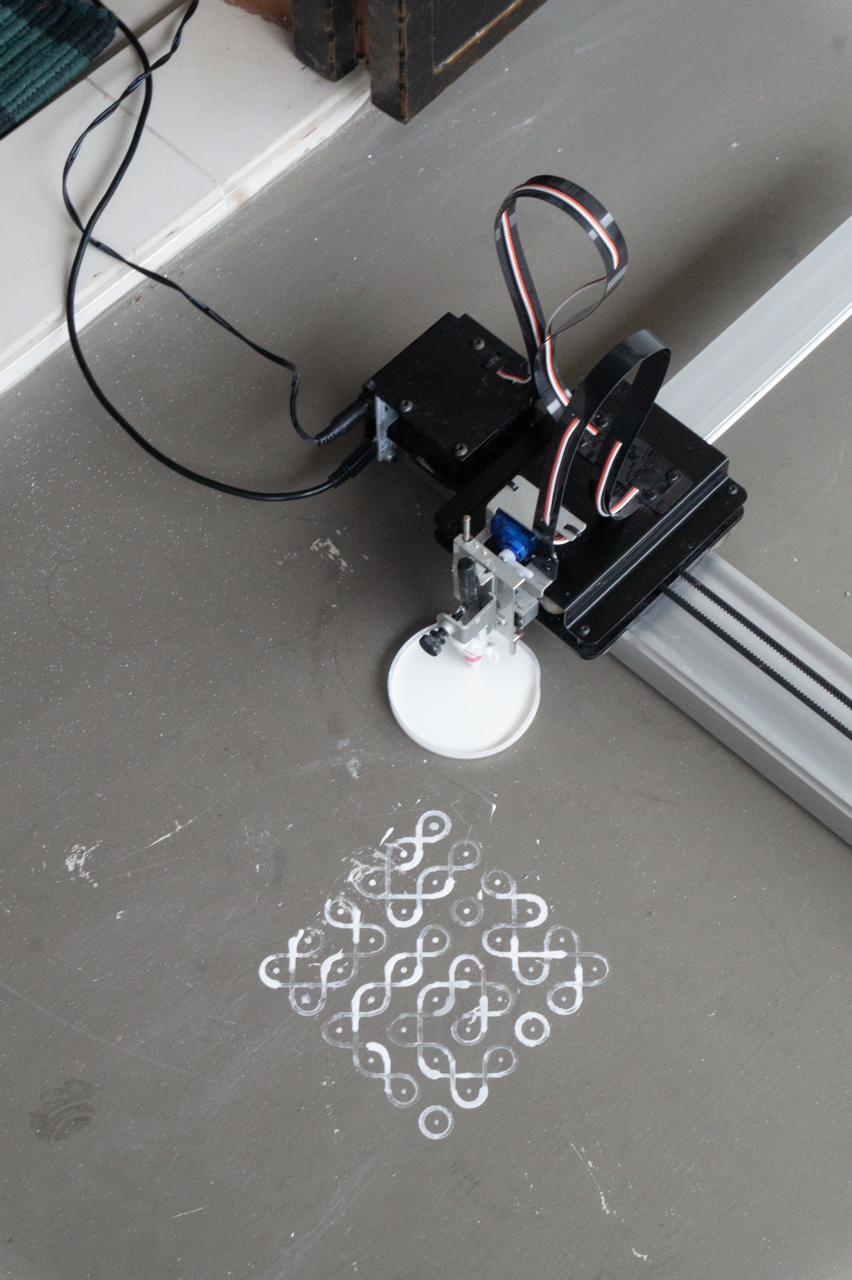

Translating these gestures into a technological context opens up both possibilities and tensions. What would it mean, for instance, to use an Axidraw plotter to draw a kolam? The Axidraw offers precision in abundance, but it lacks the embodied temporality that defines a hand-drawn kolam. It does not slow down, pause momentarily, or vary slightly in response to breath or balance. At best, such a machine might serve as a scribe, replicating a design. Yet unless its motions emulate the constraints and improvisations of the human hand, perhaps by encoding hesitation or irregularity, it risks reducing kolam to a static output rather than preserving it as a living practice.

Still, this disjunction is not necessarily a failure. It can become a site of inquiry. What gestures are lost, altered, or reinterpreted in the shift from hand to machine? What new meanings emerge when kolam is re-inscribed through algorithm and motor instead of muscle and memory?

Kolam and rangoli are often thought of as acts of hand and body: stooping, pinching, releasing, balancing symmetry with spontaneity. Yet the objects involved are not just passive tools. Rice flour, fingertips, the ground itself: each one mediates the artist’s intent through texture, resistance, and scale. In the same way, contemporary tools like code, servo motors, and pen plotters (such as the Axidraw) could extend this vocabulary. They could not simply be replacements for the hand but collaborators with different affordances.

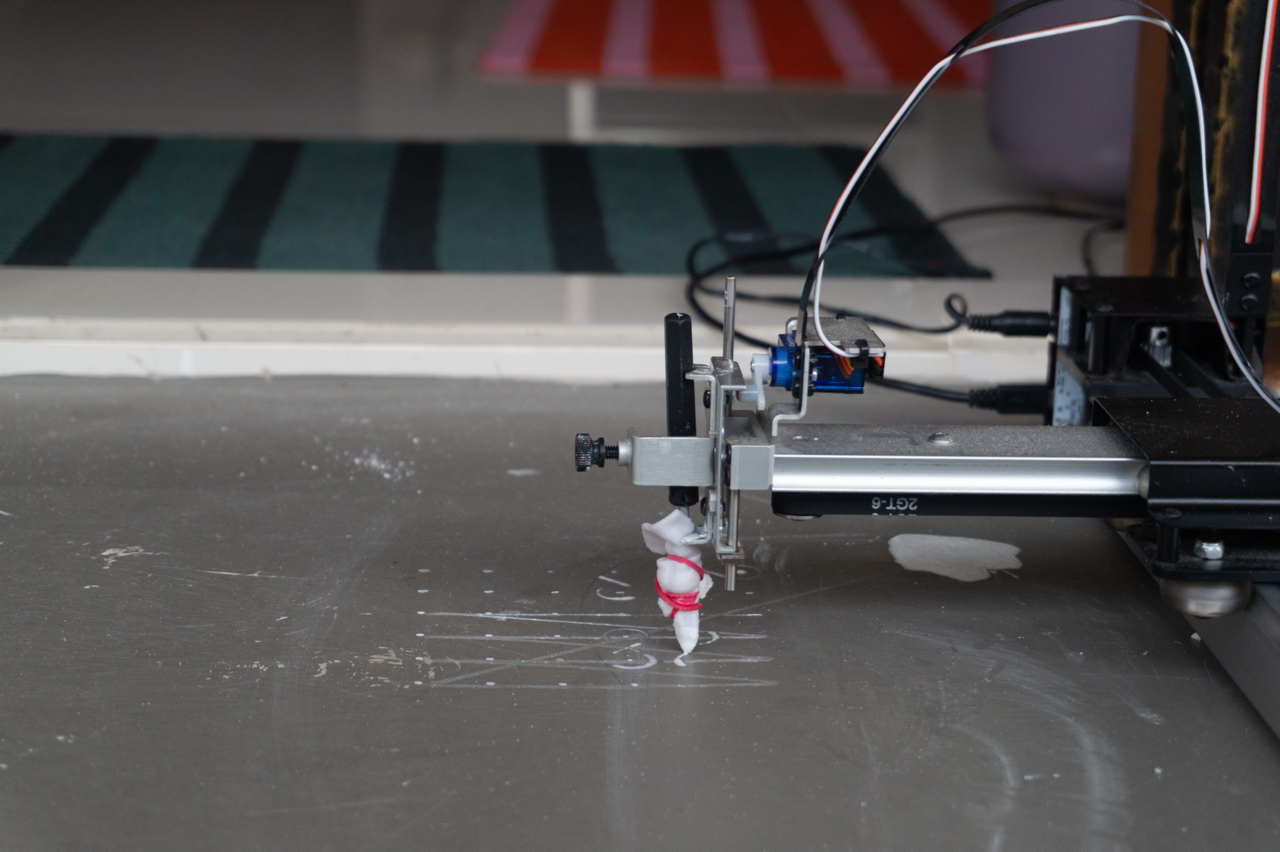

With this line of thinking, when I use an Axidraw to draw a kolam, I’m not just automating a process. I’m shifting the site of action, from muscle memory to algorithmic instruction, from intuitive curve to coordinate path. Perhaps, the result still carries human intentionality, but refracted through a mechanical logic. There is precision, repetition, even elegance, but also a new kind of uncertainty. Wet rice batter might pool, the pen might slip, the machine might misalign—introducing its own form of improvisation. These glitches are not failures but outcomes of a different kind of embodiment: one where human gesture is translated through code, then enacted by machine.

This hybrid process makes visible the layers between thought, movement, and material. Generative design and physical computing do not strip away human presence; they redistribute it. A rangoli made with a plotter still begins with choice, constraint, and curiosity. The object might be different, but the action (interpreting pattern, working with imperfection, leaving a trace) remains.

Materiality

From my perspective, as someone who lacks the years of practice than Indian woman have, making a kolam is a tactile negotiation with materials.

When I use wet rice flour in place of ink in the Axidraw, the plotter must contend with thickness, moisture, and absorbency; qualities that are far less predictable than pen on paper. The batter may clot at the nozzle, spread unevenly, or stain the drawing surface in ways that curated code cannot anticipate. From an optimistic perspective, these outcomes are not errors but expressions of a different kind of material logic, one that reintroduces texture and variability into the mechanical process. In traditional kolam-making, rice flour interacts with dust, sunlight, insects, and feet; it is not only a medium but a participant. Translating that materiality into the Axidraw’s controlled framework reveals how much a kolam is shaped by its substrate: how much the ‘ink’ matters, even when the movement is machine-led.

A collection of Axidrawn Kolams.

From household thresholds to gallery floors, each surface and context potentially invites a different reading of the work. The Axidraw operates with precision, yet the medium (imperfect, heavy, alive) introduces a counterforce. Wet rice flour pools unpredictably, lines drift, and forms emerge at the intersection of algorithm and material resistance. The result is not a mechanical imitation of hand-drawn kolams, but a reinterpretation shaped by friction, misalignment, and recontextualized ritual.